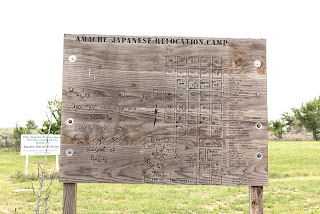

Panorama of Granada Relocation Center, Amache, Colorado, showing in the foreground a typical barracks unit ... consisting of 12 six-room apartment barrack buildings, a recreation hall, laundry and bathhouse, and the mess hall, constructed by Army Engineers. The Center is made up of 30 such blocks, complemented by hospital buildings, adminstrative office buildings, living quarters, general warehouse structures and Military Police quarters. War Relocation Authority photo.

Family Christmas Spirit

Christmas in captivity

While Colorado Governor Ralph Carr's campaign policies were aimed at dismantling the expensive bureaucracy of the New Deal, Carr still supported Roosevelt's foreign policy and favored American entrance into World War II after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The war with Japan initiated a chain of events that bred discrimination and intolerance toward Japanese-Americans.

In 1942 an estimated 120,000 Japanese-Americans were stripped of their property and possessions. These displaced citizens were resettled in land-locked states by the War Relocation Authority so that the supposed "yellow peril" could be contained. The question on many Coloradans' minds was not whether American citizens of Japanese decent should be stripped of their rights and put in internment camps, but where the camps should be. The overwhelming opinion of the populace was typified by a series of highway billboards proclaiming, "Japs keep going."

In other states, the Governors took aggressive stances against allowing relocation camps in their States.The Governor of Wyoming at the time went as far as saying:

“There will be Japs hanging from every pine tree.” If the Federal Government tried to relocate West Coast Japanese Americans there.

One of the few voices of reason during wartime was Governor Carr, who continued to treat the Japanese-Americans with respect and sought to help them keep their American citizenship. He sacrificed his political career to bravely confront the often-dark side of human nature.

At one time, the New York Times consider Carr as being on the path to become president of the United States.

"If you harm them, you must harm me. I was brought up in a small town where I knew the shame and dishonor of race hatred. I grew to despise it because it threatened the happiness of you and you and you." Carr's selfless devotion to all Americans, while destroying his hopes for a senate seat, did in the end become extolled as, "a small voice but a strong voice."