On the afternoon of February 21, 2006, Norbert Schild sat down at a desk in the reading room of the City Library of Trier, in western Germany, and opened a 400-year-old book on European geography. Working quickly, Schild laid a piece of blank white paper on top of the book, took a boxcutter from his lap, and discreetly sliced out a map of Alsace from pages 375 and 376.

Schild hadn’t noticed that the desks of two librarians, who were normally tasked with locating books for readers, were raised about three feet above the floor—giving them a clear view of his movements. They approached Schild and asked him what he was doing.

“It was worth a try,” Schild told them. He tossed his library card down on the table and hurried out of the building, taking the map with him.

Stunned, the librarians went to the director of the City Library, Gunther Franz. A mustachioed specialist in the history of the book, Franz gathered two witnesses from the reading room and filed a police report. He also emailed German libraries with a warning. Schild had introduced himself as a historian, Franz wrote, and was of medium height with a stocky build, unkempt blond hair, prominent jewelry.

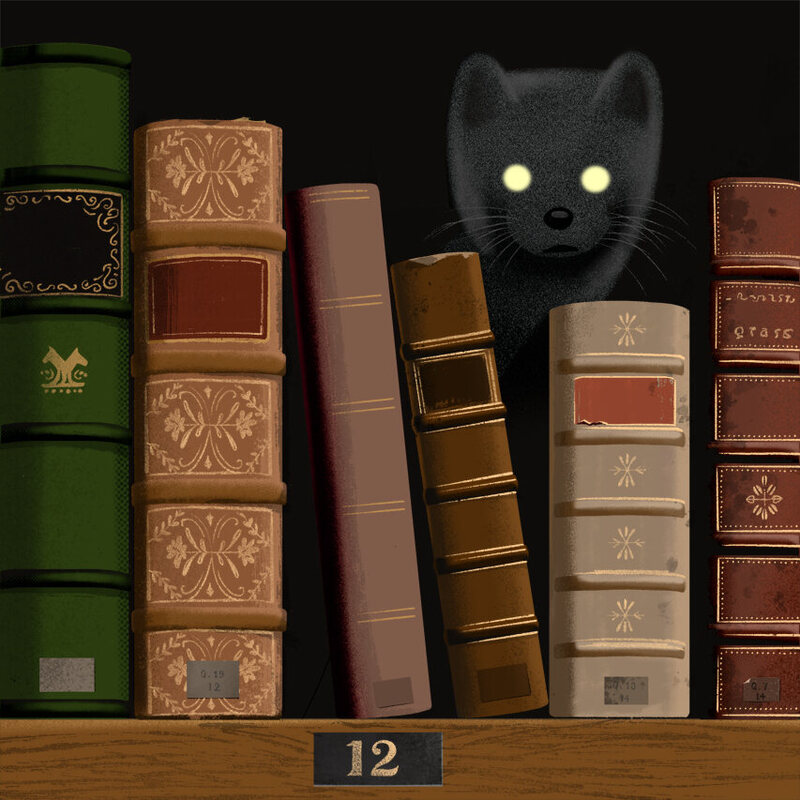

In his email, Franz dubbed Schild the Büchermarder, or “book marten.” Martens are carnivorous mammals that often steal bird eggs and are notoriously difficult to get rid of. The nickname stuck.

Almost 300 miles away, at a library in Oldenburg, a small town close to the North Sea, Klaus-Peter Müller read Franz’s email. His face went pale. He knew Norbert Schild.

The so-called book marten had been a regular visitor at the Regional Library of Oldenburg, where he had introduced himself as a doctoral student focusing on historical travel literature and atlases. Müller recalls talking with Schild about his research. “I was completely unsuspecting,” he says.

Müller and his colleague, an eloquent younger librarian named Corinna Roeder, went through their records for information about Schild’s visits. Most of it had already been destroyed: Oldenburg, like most German libraries, follows strict privacy policies. But they had one clue. Schild had last visited the library in the fall of 2005. He’d planned to come back, and the books he’d requested had been set aside.

Müller and Roeder began combing through the volumes. Two of them, including a valuable Spanish geography tome, were unharmed. The third, Louis Renard’s Atlas van Zeevaert en Koophandel door de geheule Weereldt, a sea-and-trade atlas from 1745, seemed fine at first glance—but then they looked closer.

Schild had cut out nine maps, including Renard’s rendering of the entire known world and intricate illustrations of southeast Asia and the Hudson Bay. He’d also cut out the appendix, which included the list of those maps. As if that weren’t enough, he’d also taken a pencil and numbered the remaining maps in tiny writing on the upper right-hand corner, in the manner of a professional archivist. Only an attentive reader would notice what was missing.

“I was sitting there, and I could hardly breathe,” Roeder recalls. “He was really a professional.”

Roeder filed a report with the Oldenburg police. (She later estimated the damages at between $44,130 and $48,800.) At the recommendation of an acquaintance, she also scoured online auctions for maps that could have come from the Renard book. She compared sales photos with the distinctive coloring, size, paper yellowing, and wrinkles of the Oldenburg atlas, and emailed antiques dealers, asking about the provenance of the maps on sale.

By Easter, Roeder had narrowed her search down to two sellers. On a sunny day in early May, 2006, Roeder and her colleague Klaus-Peter Müller climbed into the Oldenburg Library’s red VW Golf and drove off in search of the missing maps. “We felt like we were in a road movie,” Roeder says.

Roeder and Müller drove the 300 miles from Oldenburg to Ghent, Belgium, with Renard’s damaged atlas in the back seat. The maps at the first auction house, they soon realized, didn’t match. The size and surface of the paper was different; the missing Oldenburg original had been in better condition.

After a night in a hotel, they drove another 60 miles to Breda, Holland, where they visited Antiquariaat Plantijn, a small, well-kept antique store. Dieter Duncker, the proprietor, was considerate and spoke excellent German. He showed Roeder and Müller the documents in question. They examined the pages and took measurements.

“The four maps fit,” Roeder says with a pause, “perfectly to our atlas.”

Roeder and Müller were not the only librarians who recognized the name Norbert Schild. In 1988, Schild allegedly made off with a series of illustrations of the Rhine river from the University and Regional Library in Darmstadt. In 2002, a newly restored 1616 book by the philosopher and astronomer Johannes Kepler went missing in Bonn.

Within a month of sending his email to German librarians, Franz had gathered a list of 20 institutions that believed that Schild had stolen pages from their books. On one occasion, Schild allegedly introduced himself as a freelance arts journalist.

At the University Library in Munich, Sven Kuttner, the head of the department of old books, also received Gunther Franz’s email. In 2005, Schild had spent months in the library, claiming to be a scholar working on a bibliography of historical maps from 1500 and later. Nearly 50 books that Schild had examined were missing pages. Kuttner remembers Schild’s large rings, which he now believes had sharp edges or were used to conceal a tiny knife. “He was always making eye contact,” Kuttner says. “Back then we didn’t think much of it.”

Kuttner filed a police report and banned Schild from the library. He also purchased a scale that is accurate to a hundredth of a gram. The library now weighs rare books immediately before and after use.

After collecting accounts from librarians across Germany, Franz forwarded the allegations to the state prosecutor’s office in Bonn. An investigation had already been opened, in response to the 2002 theft of the Kepler book. Franz felt confident that charges would result. Though Schild had been active since at least 1988, Trier was the first time he had been caught “in flagranti.”

During their trip to Breda, Roeder and Müller were also optimistic. The antique map seller agreed that his pages looked like an excellent match for the missing Oldenburg documents, and he told the librarians that he would take them off the market and cooperate with an official investigation.

Duncker had purchased the maps in February 2006, at a flea market for historical illustrations in Paris. A gaunt German—probably not Schild—had approached Duncker and offered to sell him the four maps for €5,000. They didn’t exchange invoices, names, or contact details.

Some librarians criticize antiques sellers for their see-no-evil approach to historical documents. “If they don’t see anything suspicious about the book, like a library stamp, then they don’t ask where it originated,” says Roeder. When asked whether he believes the pages he purchased were stolen, Duncker answers, “How should I know exactly?”

Like it or not, there is significant international demand for antique maps. René Allonge, a lead investigator with Berlin’s art crimes unit who worked Schild’s case, says, “You think, ‘Who would bother with this? Can you even make money with it?’ Yes. There is a market.” One librarian estimates that in the late 1990s, Schild could have earned about 200,000 Deutsche Marks, or more than $100,000, per year from his alleged thefts.

All over Germany, librarians waited for the Bonn state prosecutor’s investigation to proceed. But they never filed charges against Schild. The evidence was largely circumstantial: While libraries could show that Schild used the damaged books, they couldn’t necessarily prove that he was the one cutting out the pages. A search warrant executed at Schild’s home on November 22, 2002, turned up “tools of the trade,” such as bibliographies and lists of historical materials at Germany libraries, but no actual stolen maps. Prosecutors in Bonn were busy, and the stakes may have seemed low—old books, not human lives. The charges in Trier—where Schild was caught red-handed—were dropped due to negligibility, after damages were estimated at just €500. A spokesman for the prosecutor’s office in Bonn declined to comment.

Corinna Roeder didn’t give up on the Renard atlas. In December 2008, realizing that the investigation had stalled, she began negotiating with Duncker privately for the return of the maps. When they failed to agree on a price, Duncker sold them elsewhere.

Without the support of law enforcement officials, Germany’s librarians embarked on a game of cat and marten with Schild that lasted another 13 years. In that period, Schild visited at least 15 more libraries all over the country. Twenty-two years after his first visit, he made an appointment to visit the University Library in Darmstadt. The librarians set a trap, but Schild didn’t show.

“I still regret that,” says Silvia Uhlemann, the head of the historical collections department there. That same day, Schild appeared in Düsseldorf instead. As libraries got organized, Schild allegedly began using pseudonyms and working with accomplices.

Through his lawyer, Schild declined to comment for this story unless Atlas Obscura paid for an exclusive interview.

In July 2017, Schild, this time calling himself a history professor emeritus, visited the library of the University of Innsbruck, in the Austrian Alps. After he left, a librarian named Claudia Sojer plugged Schild’s name into a library newsletter and came across the warnings. She looked through the book Schild had studied—a 1627 volume by Johannes Kepler—and realized that an engraved world map, valued at €30,000, was missing. (She had been in the room with Schild, but had left briefly for a bathroom break.) Finally, prosecutors in Schild’s home district of Witten, near Bochum, managed to bring him in front of a court on charges of theft.

Schild was now 65 years old, and his reputation as a book thief dated back over 30 years. The trial took place in April 2019. The alleged book marten had a white mustache, wore a blue blazer, and walked with the aid of a purple crutch. He told local reporters, “The charges are ridiculous,” and said that he had been looking forward to the trial.

In the courtroom, Schild sipped Diet Coke, speaking only to say that the map was already gone by the time he accessed the Kepler book. His lawyer argued that the document could have been stolen by anyone, including a library employee. A search warrant failed, again, to turn up anything at Schild’s house.

The proceedings revealed a cache of new information about Schild. He was once a salesman of industrial equipment. He has three grown children and has been married four times. His lawyer told the court that Schild had been dogged by financial worries, often taking on odd jobs to keep himself afloat.

As it turned out, Schild had been convicted of more than a dozen prior counts of theft and fraud. He usually got off with a fine or probation, but he did serve one jail sentence of a year and a half, in the early 2000s. The judge on the 2019 case, Barbara Monstadt, sentenced Schild to one year and eight months of jail time without the possibility of parole.

Corinna Roeder wishes that a similar sentence had been handed down sooner: Fines and probation didn’t stop Schild. Just days after he was caught red-handed in Trier, Schild appeared at a library in Halle. “How much mischief do you have to make to be punished, and then stop doing it?” asks Roeder.

Schild is currently appealing. “The evidence is all circumstantial,” his lawyer said after the verdict. Schild has not yet begun his sentence, and the legal proceedings are currently on hold due to his ill health: He says he is suffering from diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

A photograph of Schild, looking roguish in a suit and tie, still hangs in the Regional Library of Oldenburg. It’s on a bookshelf behind the information desk, next to the printer and some dictionaries. The photograph is out of the way and unmarked, and could even be mistaken it for a keepsake. Only library staff know that it’s a warning.