When I listen to the voice recording I made at the Irvine, California, headquarters of the video-game company Blizzard Entertainment this past January, I hear a noise that many gamers find blissful: the sound of utter mayhem. Playing a prerelease version of Diablo IV, the latest installment in a 26-year-old adventure series about battling the forces of hell, I faced swarms of demons that yowled and belched. My character, a sorcerer, shot them with lightning bolts, producing a jet-engine roar. I jabbed buttons arrhythmically—click … click … clickclickclick—while trying to stifle curses and whimpers. But the strangest sounds came from the two Diablo IV designers who sat alongside me. As I dueled with an angry sea witch, Joseph Piepiora, an associate game director, gently noted that I was low on healing potions. “But that’s okay,” he said, “because you’re conducting an interview while doing a boss fight. It’s okay.”

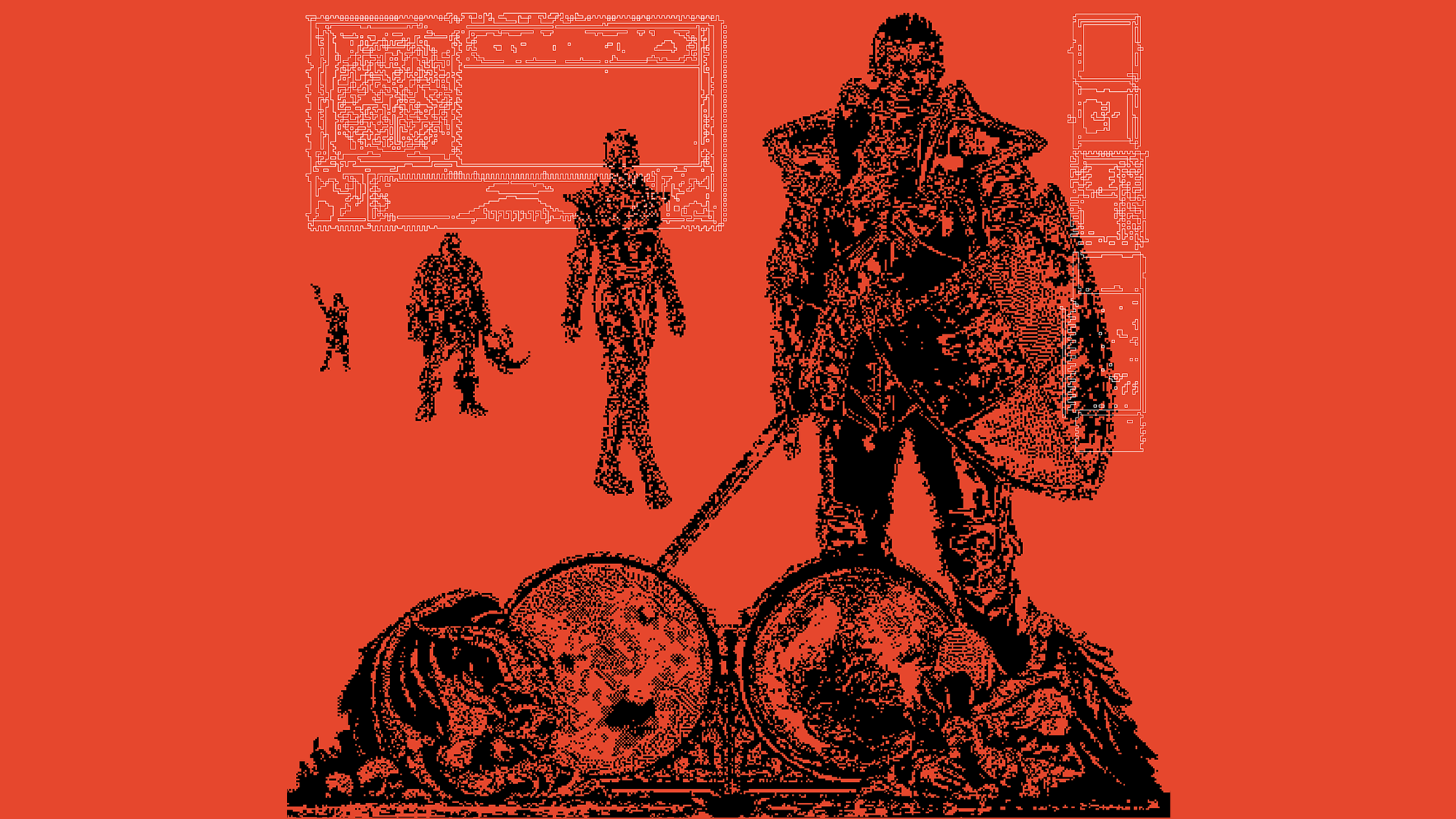

The kindness was appreciated if incongruous: The world of Diablo is violent and lonely, a classic example of the hard-core-gaming experience. Earlier editions are notorious for beckoning a certain kind of player—typically male—to hunker down alone in marathons of virtual hacking and slashing, immersed in a simplistic fantasy in which might makes right and women wear bikini-like armor. But Blizzard Entertainment is trying to show its sociable side these days. With tens of millions of monthly users of its products, the studio is one of the most important brands in gaming, an industry whose nearly $200 billion in annual revenues exceed those of the global box office and the recording industry combined. Blizzard is also a business under siege: an object lesson in how gaming’s old guard is facing new pressures.

In 2021, allegations in a lawsuit brought by California’s Department of Fair Employment and Housing against the studio’s parent company, Activision Blizzard, seemed to confirm the worst stereotypes of gaming as a realm of testosterone-fueled brutality and indulgence—and not just within the universe of the games themselves. According to the complaint, the company had become a “frat house” where female employees were underpaid, discriminated against, and groped; “women who were not ‘huge gamers’ or ‘core gamers’ and not into the party scene were excluded and treated as outsiders.” Activision Blizzard initially described the allegations as “distorted, and in many cases false,” a response that the company’s CEO soon after called “tone deaf.” The suit is still in litigation, but a number of company leaders have departed since it was filed, including developers originally tasked with steering Diablo IV, Blizzard’s most anticipated new title in years.

The company has pledged to hire more women, treat employees better, and make more inclusive products—all while being vetted for a $68.7 billion acquisition bid by Microsoft, a deal that regulators are scrutinizing, wary of the market power that the resulting megacorporation could wield.

“It’s taking time for us to grow up,” Rod Fergusson, Diablo’s general manager, told me. By “us” he meant the industry at large. No longer the niche activity it was when Blizzard was founded in 1991, gaming has become a mass pastime (two-thirds of Americans participate) and a diverse one (nearly half of gamers are women). New and so-called casual users, many playing on their phone, have driven the sector’s surging growth. But the mainstreaming has triggered purist pushback, tinged with machismo and aggression. In the mid-2010s, the “Gamergate” campaign saw hard-core players systematically harass “fake gamer girls” who dared to denounce, say, the “jiggle physics” commonly used in the animation of female characters across the medium. Multiplayer-chat channels remain, as ever, rife with bigotry and sneers at “newbies.” The allegations against Activision Blizzard, along with recent harassment scandals at a number of other prominent companies, suggest an intractable culture. Gaming’s association with antisocial, immature dudes is dying hard.

I visited Blizzard’s headquarters because, to tell the truth, I was once an antisocial teenage dude who spent a lot of time with Diablo II, the 2000 iteration of the franchise. Playing as an ax-wielding barbarian with bulging muscles, I slashed across screens full of monsters, striving to acquire power (by gaining experience points) and lucre (gold, gems, and gear dropped by vanquished foes). The franchise’s creators had wanted the time “from boot-up to kill” to be less than a minute, and for combat to reward players like slot machines reward gamblers. The resulting rhythm of pummeling and prospering—the game’s “core loop,” to use an industry term—was more validating than anything in my real life as a high schooler. I was so hooked that I eventually decided to quit the game cold turkey, fearing that my schoolwork and friendships would wither away if I didn’t.

[From the October 2021 issue: Confessions of a Sid Meier’s Civilization addict]

Ostensibly, the industry has changed a lot since then. The first Diablo sequel in 11 years is being released by a scandal-chastened company touting a PR-savvy mission to “foster joy and belonging for everyone,” as Blizzard’s president, Mike Ybarra, put it to me. The goal is to appeal “to as many players as we could possibly think of, because we want this game to be inclusive,” another Diablo team member said. But as it turns out, Diablo’s hard-core-friendly hellscape hasn’t been reformed so much as made roomier. For Blizzard, is growing up really about finding new ways to grow its bottom line?

Blizzard has already helped shape and reshape the idea of what video games are and who plays them. By pairing vibrant, inviting aesthetics and fanaticism-inducing complexity, the early hits Warcraft (1994), Diablo (1997), and StarCraft (1998) created masses of devoted gamers in the first generation to come of age with PCs. But Blizzard’s most significant contribution to gaming may have been its 2004 smash, World of Warcraft, which instilled the idea that games could serve as virtual communities.

A “massively multiplayer online role-playing game,” World of Warcraft offered a sprawling environment populated by hundreds or thousands of other human-controlled heroes who were encouraged to quest together. Fostering an online civilization where one can feel like both a fearsome mage and an admired camp counselor, the game became an example of how to profitably fulfill the cravings of multiple constituencies: By 2009, it was the most popular paid title among women ages 25 to 54.

Smartphones and social media brought new users into gaming’s fold—many of them more interested in camaraderie and creative expression than combat. Across a range of tried-and-true genres, video-game designers took the Hollywood-blockbuster approach, creating games that catered to mixed audiences: male and female, old and young. Well-populated virtual playgrounds such as Epic Games’ Fortnite—in which scores of competitors trade bullets, banter, and funny dances, much to the derision of hard-core gamers—have contributed to the doubling of global gaming revenues since the mid-2010s.

This influx of new players brought with it new tensions. As Blizzard unsteadily adjusted to the marketplace it had helped create, the company started to face criticism from multiple directions. The streamlined gameplay and brighter-hued, somewhat-cute visual style of 2012’s Diablo III angered many veteran gamers by appearing to pander to newbies. Yet soon after that, to the dismay of some female fans, Chris Metzen, then a vice president at Blizzard, referred to a new World of Warcraft storyline as “a boys’ trip.” Elizabeth Harper, the editorial director of the fan site Blizzard Watch, told me she recalled having “a sinking feeling” about his remarks: “He’s up onstage saying, Yeah, this is a ‘no girls allowed’ club.” Eight years later, the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing’s allegations against Activision Blizzard suggested that the club was alive and well.

In making inclusion central to its pitch for Diablo IV—“Hell welcomes all,” goes one marketing tagline—Blizzard has introduced some cosmetic changes. You can customize your barbarian avatar to appear nonbinary, if you so choose. The game’s lead villain, the ram-horned demon Lilith, might even be seen as a strong (if, alas, homicidal) female character. More notable, however, are the structural changes, which take their cues from World of Warcraft ’s capaciousness and encourage more varied, and social, styles of play.

Rather than move through a linear sequence of challenges, players roam a sprawling “open world,” tackling quests in whatever order they want, or ignoring them altogether. This format has its appeal for hard-core completists—after all, it multiplies the number of missions to master—but Ash Sweetring Vickey, a producer on the game’s dungeons team (which endows ghoul-infested caverns with the thrilling infinitude of a casino floor), pointed out that it’s also great for low-stress time killing. “If I wanted to go spend a hundred million hours just looking at wraiths in the wild, I could do that,” she told me.

For veterans, the most controversial development is who resides in this open world: throngs of gamers adventuring all at once. Many fans relished playing previous editions of Diablo solo, fulfilling the fantasy of being a lone savior overcoming immense odds. But in Diablo IV, some key areas are populated with the avatars of other players. In theory, you can ignore these avatars, but the game nudges you to engage with them by featuring a few gargantuan monsters who are nearly unbeatable on one’s own.

“We got pushback from people who heard about the shared world,” Fergusson, the general manager, said. “They were like, ‘I don’t want to see other players. I want to be alone. This is my journey.’ ” Last fall, the fan site Pure Diablo published an open letter to Blizzard, advising against so-called forced multiplayer. “Focus on making the game a … game!” one commenter wrote. Meaning: Keep it old-school; don’t turn it into a social network.

But the business rationale for mandatory online play could hardly be clearer, as the makers of World of Warcraft learned long ago and as recent juggernauts such as Fortnite have confirmed. (A social environment also entices players to pay for extra content, such as the “cosmetic upgrades” that will be available in Diablo IV—don’t you want to be the best-dressed sorcerer in the land?) Ybarra, Blizzard’s president, mentioned wanting to eventually reach 1 billion people with Blizzard’s games—which means that serving hard-core players alone is not the main quest.

Yet Blizzard isn’t ditching the old guard, and has crammed Diablo IV with elements they crave: endless options for combining weaponry and gear; beasts that get smarter and meaner as you progress; amped-up scariness and gore. (I nearly gagged while fighting through a dungeon encrusted with festering intestinal pustules.) Reconciling obsession-breeding depth and intensity with buffet-style breadth and access was, the developer Piepiora told me, the main design challenge: “trying to take the ideas of this massive, interconnected world and meaningfully tie them back to the core loop.” The hope, in other words, is to extend the game’s allure while strengthening the cycle that potentially turns newbies into addicts of the bashing and looting that was, and remains, Diablo’s essence.

The end product is a bit surprising for a company that aims to present itself as emerging from scandal and eager to foster joy, in Ybarra’s words. Diablo IV is bleaker, eerier, and perhaps even more mania-inducing than any earlier installment. In the hours I spent playing it, I fell under the same spell I did as a teen. My character traversed a nightmarish realm, strewn with the ruins of villages (Don’t forget to inspect the corpses of the villagers for gold, I told myself). When other players flitted by on the battlefield, they didn’t alter my trajectory or jolt me out of my hypnosis. I had no idea who my peers in demon-slaying were; they had customized their appearance and were embarking on bespoke adventures. What I did know was that they were doing exactly the same thing I was doing: click … click … clickclickclick.

This article appears in the July/August 2023 print edition with the headline “‘Hell Welcomes All.’”