Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and/or images of deceased people.

Images of mounted police contending with anti-lockdown protesters on the weekend have now gone viral around the world. In fact, mounted police have a long history in Australia.

They have certainly been used as a method of crowd control at countless demonstrations in living memory — from anti-war protests to pro-refugee rallies and everything in between.

But the history of mounted police in Australia goes much deeper.

Read more: Enforcing assimilation, dismantling Aboriginal families: a history of police violence in Australia

Mounted reconnaissance and messengers

In early colonial Australia, horses were at a premium. In the 1790s, policing of convicts and bushrangers in the confined region of the Sydney basin was conducted on foot by night watchmen, constables and the colonial military.

By 1801, the then Governor King formed a Body Guard of Light Horse for dispatching his messages to the interior and as a useful personal escort.

By 1816, at the height of the Sydney Wars of Aboriginal resistance, the numbers of horses in the colony had grown.

Their importance as mounted reconnaissance and for use by messengers was critical to Governor Macquarie’s infamous campaign, which ended in the Appin Massacre of April 17, 1816.

The horse as a key element of occupation

Along with firearms and disease, the horse was a key element in occupying Aboriginal land and controlling the largely convict workforce on the frontier.

In the early 1820s, west of the Blue Mountains, the use of horses in the open terrain of the Bathurst Plains was critical in capturing escaped convicts and bushrangers, as well as defending remote outstations against attacks from Wiradjuri people.

Early intrusions into Wiradjuri land were not so much by British colonists, but by the animals they brought with them. In what is now recognised as “co-colonisation”, cattle and sheep did a lot of the hard yards for the British, often well before they arrived in Aboriginal lands.

In 1817, Surveyor General John Oxley thought he was well beyond the limits of settlement when, as he wrote:

to our great surprise we found the distinct marks of cattle tracks [that] must have strayed from Bathurst, from which place we were now distant in a direct line between eighty and ninety miles.

From a colonial cavalry to mounted police

During the first Wiradjuri War of Resistance between 1822 and 1824, calls were made to the colonial authorities for the formation of a civilian “colonial cavalry” to assist the beleaguered and overstretched military forces. My (Stephen Gapps) forthcoming book, developed in consultation with Wiradjuri community members in central west region of NSW, The Bathurst War, looks in deeper detail at this period.

It was hoped colonial farmers would be their own first line of defence against Aboriginal warrior raids on sheep and cattle stations.

Governor Brisbane wrote to London that in 1824 a mounted force was becoming “daily more essential [for the] vital interests of the of the Colony”.

But by August that year, heavily armed and mounted settlers, overseers and their armed convict workers had decimated Wiradjuri resistance before a formal cavalry militia was established.

After possibly hundreds of Wiradjuri people had been massacred by heavily armed and mounted settlers, a “Horse Patrol” was created in 1825, which soon formally became the Mounted Police.

The Mounted Police were critical during a spree of bushranging soon after — a largely unanticipated side-effect of arming of convict stockworkers to defend themselves against Wiradjuri attacks in 1824.

By the 1830s, the force had proved useful as a highly mobile quasi-military unit in combating Aboriginal resistance as well as bushranging.

As the colony continued to expand with an insatiable desire for running cattle and sheep on Aboriginal lands, three regional divisions were based at Bathurst, Goulburn and Maitland.

After conflict between colonists and Gamilaraay warriors on the Liverpool Plains, commander Major Nunn led a Mounted Police detachment on a two-month campaign around the Gwydir and Namoi Rivers, resulting in the Waterloo Creek Massacre on January 26, 1838. Armed colonists soon followed suit, ending in the Myall Creek Massacre in June that year, where colonists killed at least 28 Aboriginal people (possibly more).

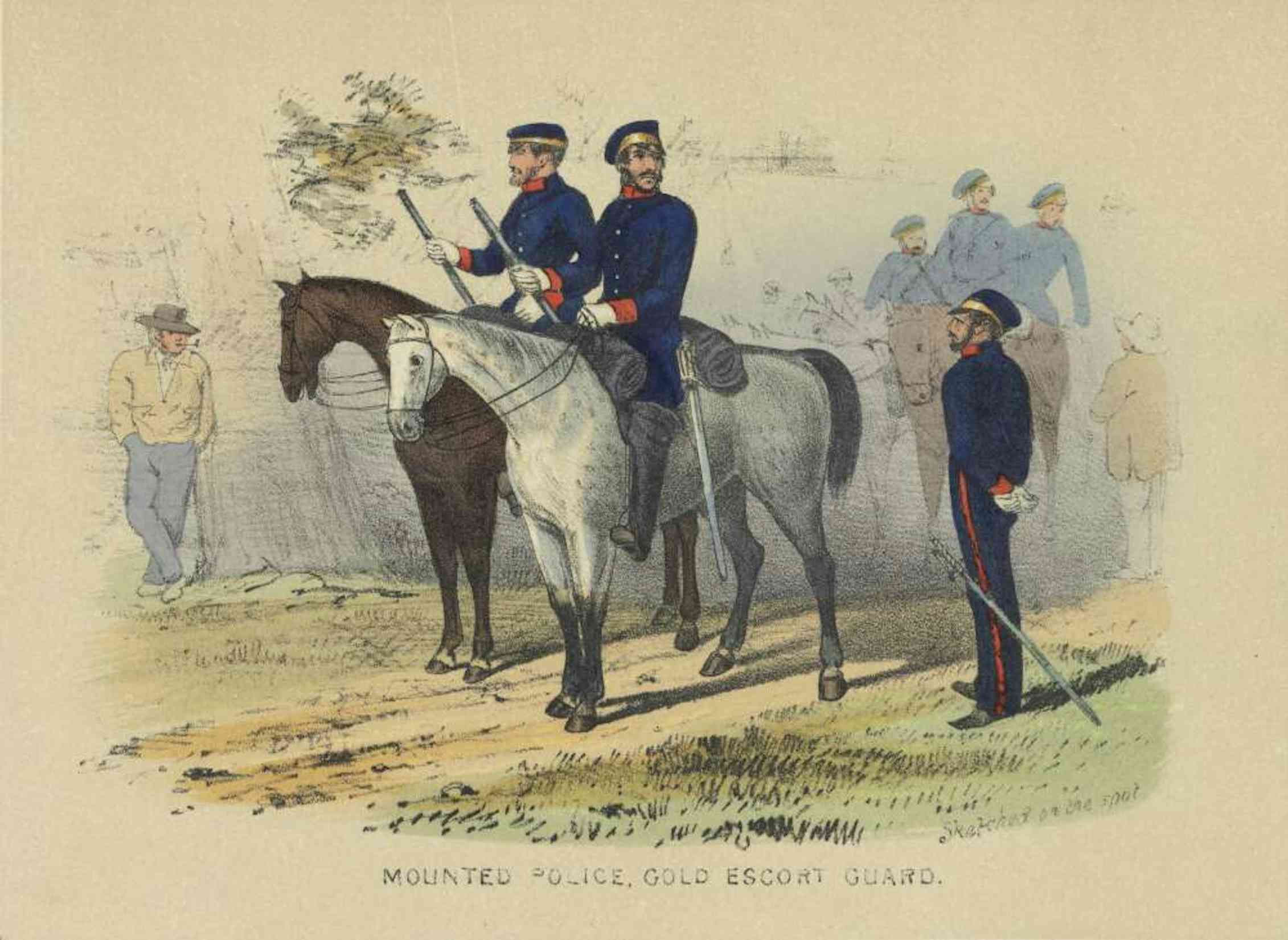

The Mounted Police’s military functions came with heavy expenses, which included uniforms, equipment and barracks. During the 1840s, a Border Police force of ex-convicts equipped only with a horse, a gun and rations was created and attached to Commissioners of Crown Lands.

It was funded by a tax on squatters (whose interests they protected) and proved a much cheaper policing option for the frontier.

The Native Mounted Police

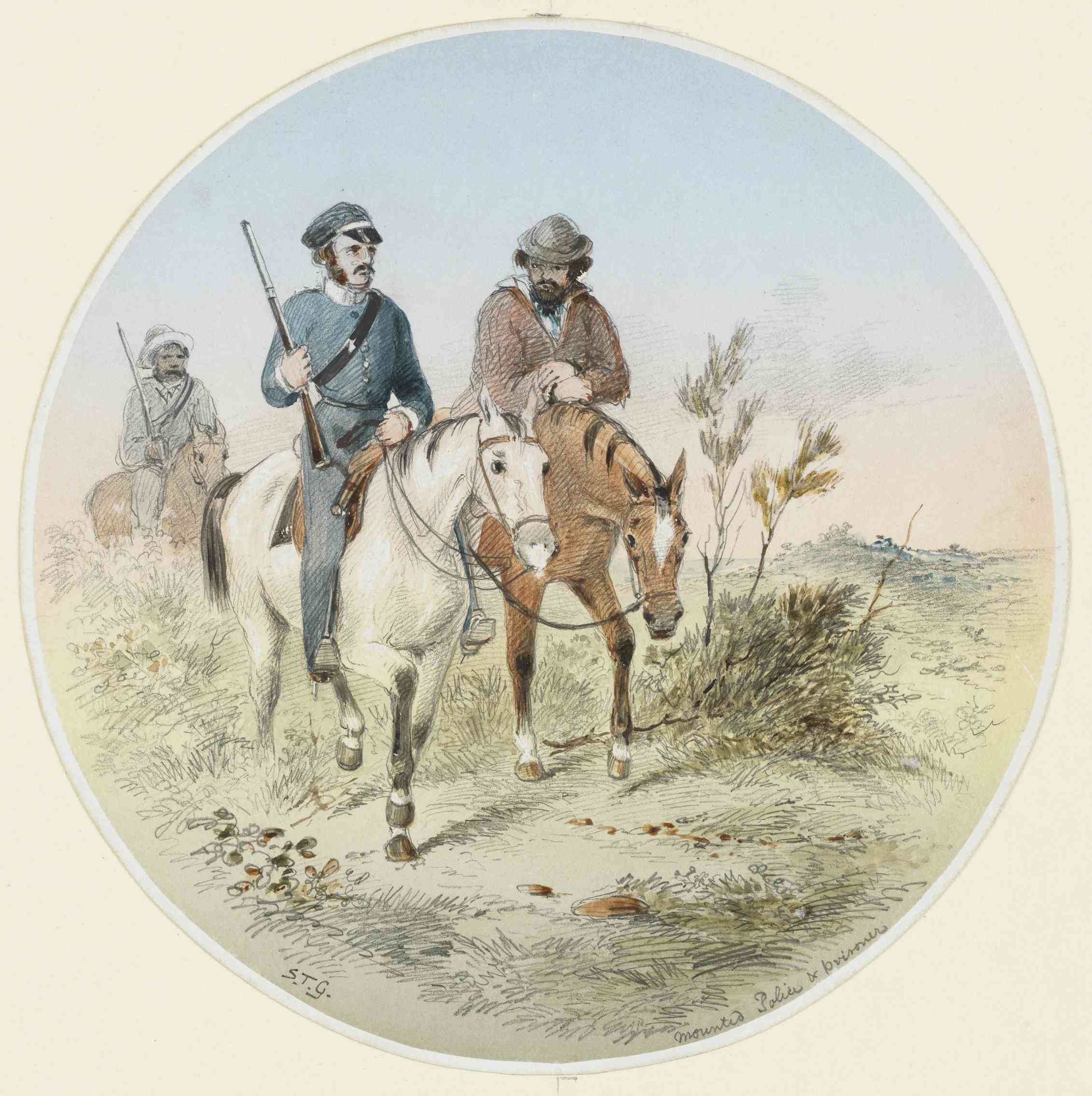

By 1850 the “Mounted Police” were disbanded. Another relatively cheap and what proved to be a tragic, if remarkably successful, option had been found — the creation of a “Native Mounted Police” force of Aboriginal men with British officers.

The troopers were provided with uniforms, guns and rations. By the 1860s, particularly in Queensland, the main problem on the frontier was not policing colonists but stopping Aboriginal resistance. So arming Aboriginal fighters was part of a tried and tested British method of exploiting existing hostilities by rewarding those who collaborated and punishing those who resisted.

As Bogaine Spearim, Gamilaraay and Kooma man, activist and creator of the podcast Frontier War Stories has noted, the Queensland Native Mounted Police (NMP) were not only feared by bushrangers such as Ned Kelly, but known for their violence toward the Aboriginal population of Queensland.

The NMP united incredible bush skills with military capability. Their legacy has been the focus of a recent project by Australian researchers Lynley Wallis, Heather Burke and colleagues.

The role of animals in colonisation and policing

From 1850, the colonial police force (and then from 1862, the NSW Police force) incorporated mounted police as mobile units in mostly remote locations.

But they also found them useful in urban areas, especially with growing numbers of strikes, political disturbances, protests and riots in the rapidly industrialising cities in the late 19th century.

The use of horses in crowd control has a long history in policing, which itself has a long history in warfare. Among the other issues this presents, we might also consider horses’ long suffering histories of being placed in the front lines of conflict.

Like the inexorable march of sheep and cattle as part of the invasion of Aboriginal lands, understanding the role of animals in colonisation and policing is crucial to a broader understanding of Australian history.

Read more: Make no mistake: Cook’s voyages were part of a military mission to conquer and expand

Stephen Gapps is affiliated with the University of Newcastle and is a Senior Curator at the Australian National Maritime Museum. He is the author of The Sydney Wars (NewSouth Books) and of the forthcoming book, Gudyarra - The First Wiradjuri War of Resistance, the Bathurst War 1822-1824, which was developed in consultation with Wiradjuri community members in the central west region of NSW.

Angus Murray does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.